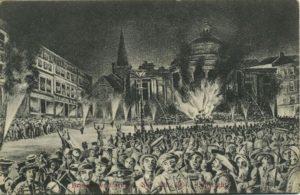

For Bridgwater, it all began with a huge bonfire at the Cornhill in the town centre. It was huge, at least twenty-four feet across the base. A hundred old tar barrels and disused tar-soaked rowing boat formed the foundation of the bonfire. So strong was the tradition of using old boats that as the river trade diminished and old boats became scarcer, it was not unusual for perfectly serviceable boats to be ‘acquired’ without the owners’ permission. Other unusual items often found their way to the bonfire and one year included a piano. In latter years it became organised and the lighting of it was arranged by the Vicar of St. Mary’s.

For Bridgwater, it all began with a huge bonfire at the Cornhill in the town centre. It was huge, at least twenty-four feet across the base. A hundred old tar barrels and disused tar-soaked rowing boat formed the foundation of the bonfire. So strong was the tradition of using old boats that as the river trade diminished and old boats became scarcer, it was not unusual for perfectly serviceable boats to be ‘acquired’ without the owners’ permission. Other unusual items often found their way to the bonfire and one year included a piano. In latter years it became organised and the lighting of it was arranged by the Vicar of St. Mary’s.

In 1847 Richard Chedzoy and James Duckham foolishly threw full tar barrels onto the bonfire. As the burning pitch melted, like molten lava, it poured from the barrels and flowed towards shop premises in the town centre. The two men were arrested and tried. Found guilty and unable to pay their 50 shilling fines, they spent the next six weeks in gaol at Wilton, being released just in time for the Christmas Festivities.

To get the fire started, something like fifteen gallons of paraffin were thrown onto the bonfire and a group of young lads with tapers alight would approach and ignite the fire. This was not a particularly safe practice since the initial burst of flames would shoot some two hundred feet into the air and could allegedly be seen from South Wales. The heat was so intense that the nearby shops would board up their windows and hang wet tarpaulins over them to prevent damage.

The Cornhill bonfire was not the only one in the town, but it was the one around which the procession centred and was the one which triggered the procession in the very early years of the celebration. On occasions it was used as a way for groups to publicly express their anger with individuals who it was felt had let down the community. In 1860 an effigy was produced of a worker from the carriage works. It appears this fellow had brought about the dismissal of a number of his colleagues, who took their revenge by parading his effigy, labelled “A traitor to his shop mates”, through the streets before committing him to the flames of the Cornhill bonfire. In 1867, in similar fashion, a farmer titled “The King of Dunwear” was given the same treatment in this 19th century equivalent of “Naming and Shaming”.

In 1872, the Cornhill bonfire was host to the effigy of someone called the Yard Spy, presumably a reference to a tell-tale brickyard worker. The Salmon Parade bonfire was host to Brother B and Sister S, a widower and seaman’s wife accused of extra-marital relationships. Even as late as 1906, an effigy of the minister of the Baptist Church was committed to the flames. He had unsuccessfully attempted to stop the pubs opening late on carnival night! What a contrast to the 1946 vicar of St. Mary’s Churchwho, referring to the carnival procession in his Sunday morning service, told the congregation how he was so impressed, he went home and went down on his knees to thank God that he lived in such an age as this.

Text Copyright © 2008 Roger Evans