In 2017 the last part of Bridgwater’s Northgate Workhouse was demolished to make way for a school. This web site tells the story of why such a cruel system was devised and tolerated and eventually brought to an end.

The Victorian workhouse system was introduced into Britain in the 1830s when the Whig (Liberal) Government of the day, in bolstering the power of the rising middle classes (the working class couldn’t vote of course) made a historic compromise with the Tories, scrapped the old “poor law” and introduced a “new poor law”.

The idea behind this new system was to deal with the poverty that had been exacerbated by the rise of capitalism, by blaming the poor. The tactic was to humiliate, shame and blame the poor for the dire condition they found themselves in.

A NEW “POOR LAW”

Of course, the other agenda for the ruling class was to reduce their own financial contribution to any poor relief. By abolishing the “poor law” – whereby poor people were provided “outdoor relief” i.e. in their own parishes, the new system introduced “indoor relief” which meant they were herded into newly built workhouses which they had to attend in order to qualify for the new “indoor relief”.

These new workhouses were in effect no more than open prisons and the “Board of Guardians” that controlled their lives were of course nominated from the local middle classes whose aim was to provide the minimum of care for the minimum of taxation and elected by rate payers, with higher rate payers having more votes. Nobody actually receiving poor relief was of course meant to have a vote.

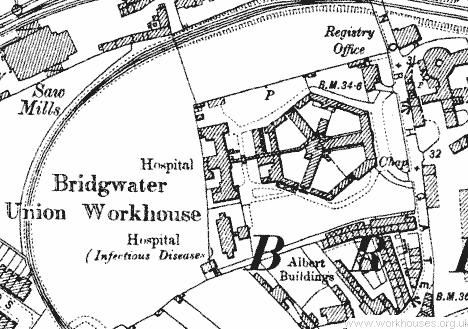

The “Board of Guardians” represented an area defined as a “Poor Law Union”. In the case of Bridgwater it basically matched current day south Sedgemoor (or “Greater Bridgwater”) and, in an ominous foreboding of today’s power share, the overwhelming majority of “Guardians” were from “out of town” – 48 elected “Guardians” from 40 Parishes – hence that bit more Tory.

HARSH CONDITIONS

Conditions were harsh. In tune with Victorian morality, families were separated to prevent “degenerate behaviour” (which meant poor people having sex) and any increase in the birth-rate. The workhouse regime was purposefully brutal and designed to terrify people so they’d do anything to avoid it.

But the workhouse system was a pointless symbol of the devastatingly failing class chasm that permeated the 19th century world. One third of the population was already in poverty, living amidst massive overcrowding, several families to a room, high infant mortality and people dying of poverty related illnesses in grim conditions airbrushed from the lives of the Victorian middle classes who were deluding themselves with glorious tales of Empire and the wealth it made (for them).

At its height the 19th century saw 700 workhouses housing 250,000 people with some, such as Lambeth in London, holding up to 1,000 people at a time – including for instance the famous comedian Charlie Chaplin. Workhouses were meant to teach you obedience and respect for the system. Chaplin remained a lifelong socialist.

WORKHOUSES IN BRIDGWATER

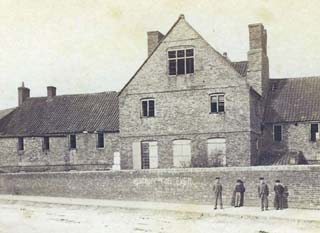

In Bridgwater there was a historic group of alms houses and a primitive workhouse already in existence by the time of the New Poor Law. The small island of buildings at the end of St Mary Street opposite the Blake Hall, was the towns original Parish workhouse (housing 86 inmates) and dated from 1693.

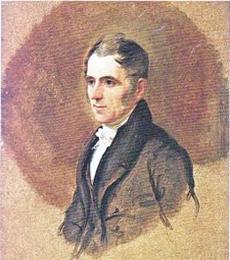

Conditions here were hellish and a major scandal erupted when numerous inmates died in a cholera epidemic, highlighted by local newspaper owner and industrialist John Bowen (he had a local paper called “The Alfred”) and who continued his opposition to the “new” poor law describing the new workhouses as “murderous pest houses” and in one attack asked, “is killing in an Union workhouse criminal if sanctioned by the Poor Law Commission?”

Bowen was scandalised at the high mortality rate “27 deaths in 6 months” and “94 deaths from dysentery caused by a change to a cheaper diet”. Meanwhile the Governors congratulated the workhouse chairman “for saving £4,843”.

On 11th May 1836 the Bridgwater Poor Law Union was established, representing a local population of 28,566 of which Bridgwater comprised 7,807 and in 1837 a new workhouse was built in shining white stone on the Northgate site with its entrance opposite the Chandos Glass Cone.

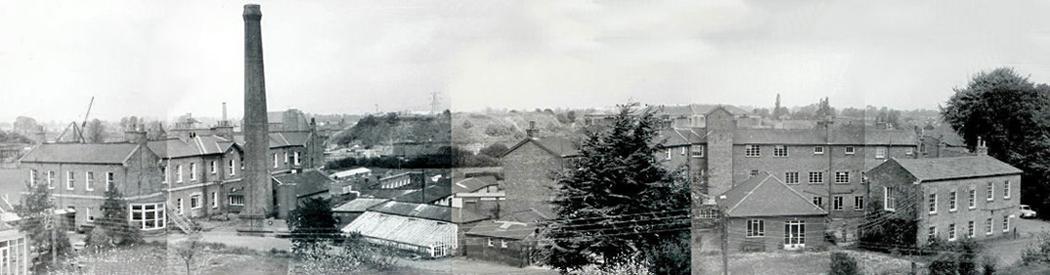

This Y-Shaped 3 storey hexagonal fortress designed to an “off the peg” specification by workhouse architect Sampson Keenthorne (he also had a “square” option but both involved creating segregated exercise yards for the different classes of inmate – Keenthorne himself emigrated to New Zealand where he lived out his days in a delightful wooden cottage) was joined by the current 2-storey Hospital section and the single storey infectious diseases isolation unit.

The bulk of the workhouse was demolished in the 1960s to absolutely no clamour for its retention and the people it had symbolised working class oppression to for years were glad to see the back of it.

THE WORKHOUSE REGIME

For inmates of the workhouse the routine was harsh. Presided over by a Master and a Matron, usually lower middle class martinets brought in purposely to be oppressive, the inmates would have anything private taken from them and forced into the workhouse uniform of brown dress and white pinafore (maybe just the women). Physical punishment was commonplace. Regular beatings in gymnasiums that doubled as punishment blocks with other inmates obliged to watch.

Inmates of the workhouse had to work for their poor relief. While the women did the cooking, laundering and sewing, the men performed physical labour, stone breaking or bone crushing.

Food was provided – 3 meals a day – largely prescribed dosages of gruel (a watery porridge) and bread with occasional bits of meat.

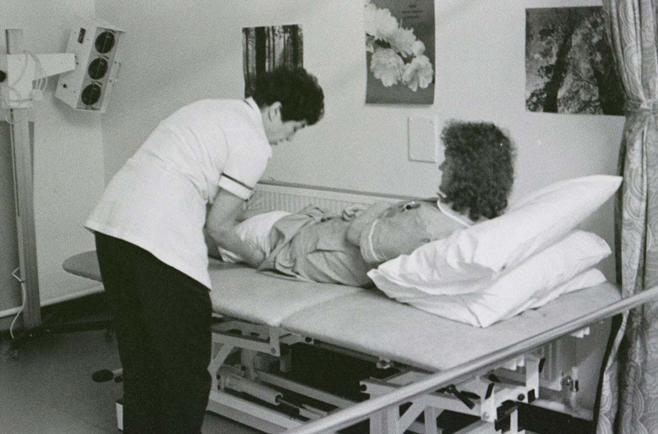

Medical provision was often dire with the nursing duties performed by elderly female inmates. Conditions were cramped and ventilation inadequate. Pain was treated in the hospital with opium, physical exercise became the treatment in lieu of any kind of therapy and with regard to death, under the terms of the new poor law (Anatomy Act 1832) anyone who couldn’t afford a funeral could be legally sent off for dissection to help medical research, the act declaring “for the crime of poverty you will be dissected to repay your welfare debt”.

The system was all about the “deserving” and the “undeserving” poor – an attitude that prevails to this day, only now we have the Daily Mail and the Sun to tell us who’s who.

HOW DID WE LET SUCH A SYSTEM HAPPEN?

The 1830’s was the key decade here. The Great Reform Bill of 1832 saw an extension of the voting rights – but just to the Middle class. The Tories of the Duke of Wellington resisted this fearing a collapse of law and order and an opening of the floodgates to the “scum of the earth”. However, due to the historical compromise between the two ruling parties the Whigs got their way having watered down the clauses so as not to upset a large number of Tories.

The prime mover was the Prime Minister Earl Grey (yes, famous for the tea) – a man so afraid of the looming working class population boom that him and his wife had 17 children. This meant that his wife was constantly pregnant and naturally he had to solve that by having numerous additional affairs.

However, the older he got the more nervous about what his very minor actions towards voter enfranchisement might have let loose and so he handed over to a more cautious Whig – Viscount Melbourne, who oversaw the introduction of the new poor law.

Melbourne – in his youth a “mate” of the radicals Byron and Shelley, inevitably got more conservative in his old age and was well known for “finding common ground”. Which came in useful when despite a sex scandal involving spanking sessions with aristocratic ladies and the whipping of orphan girls who he had taken into his household, he still remained Prime Minister, as “nobody seemed that bothered”. His main achievement was “Poor Law reform” – by which he meant “restricting the terms on which the poor were allowed relief and the establishment of compulsory admission to workhouses for the impoverished”.

Sound policies the Tories could support. The whole Middle Class intelligentsia were with him on this one. Whether it was Thomas Malthus (who Dickens satirised with his character Scrooge) and his dire warnings that “population was increasing faster than resources so we better lock the poor up in workhouses” or Jeremy Bentham’s “the poor would rather do whatever they found pleasant rather than work, so we better lock them up in workhouses” the laws went through Parliament almost unopposed.

THE PEOPLE FIGHT BACK

But they were opposed by some. Of great credit are the small group of radicals such as William Cobbett who believed the poor “..had an automatic right to relief” and “that the Act aimed to enrich the landowner at the expense of the poor” or John Fielden who saw no difference between Tory and Whig saying he would resist a law “based upon the false and wicked assertion that the labouring peoples of England were inclined to idleness and vice”.

The working class couldn’t vote, but the 1830s also saw the dawning of the Trades Union movement, with the launch of the campaign around the Tolpuddle Martyrs in 1834 and the rise of the mass working class Chartist movement, many meetings of which were chaired by John Fielden.

In some places workhouses were attacked and Poor Law Guardians often had to be protected by Police and troops. Incidences included the Plug Riots in Stockport and the Rebecca Riots in Carmarthen.

THE END OF THE WORKHOUSES

The workhouse system was finally abolished in 1929 as the extension of democracy to the working classes had led to a greater outcry against its iniquities and by 1948 it had completely been replaced by the Labour Government’s new National Health Service.

In Bridgwater the Blake Hospital thereafter became a geriatric hospital within the NHS and survived into the 21st century as a social services department of Somerset County Council where the grounds that had contained the original workhouse thence contained new buildings that made up their “Enterprise Centre”.

The final part of the Northgate Workhouse was demolished and replaced by the Northgate Primary School in 2017

BREAKER MORANT

It was in the Bridgwater workhouse that the infamous “Breaker” Morant was born. The son of the Master and Matron of the Workhouse and not an “inmate”, he moved out of the workhouse accommodation to the pleasantry of Bradford Villas in Wembdon and by the age of 19 had emigrated to Australia anyway, throughout his life denying any connection with Bridgwater and to his dying day telling people he was in fact the son of a famous Admiral.

Morant was shot as a war criminal during the Boer war and portrayed by Edward Woodward in a film made in 1980. Read more about “the Breaker”…

Text © Brian Smedley, 2017